Music Decorations and Tagging

A quick picture identifying the various segments and source of information used to decorate music in this application server.

Let now go deeper into what each of those boxes mean.

Maps

Maps are the key element for work associations. Those are essentially CSV files that uses various techniques to extract identifiers, whether it is an opus number or, for example, Kochel catalog number for a Mozart symphony.

The main one, and the one only currently in use, maps composers and a series of regular expressions to infer the catalog numbers placed from the most complex to the simple ones.

Opus and WoO (Work Without Opus)

Opus numbers are NOT tied to specific composers as it applies to any potential composers. Example of expression for opus numbers:

Extraction: *OP\.?\s?0*(?<id>[1-9][0-9]*[a-z]*)/0*(?<sub>[1-9][0-9]*[a-z]*).*

Normalization expression: Op. ${id}-${sub}

This would match op.34c/16b and normalized to Op. 34c – 16b. Other expressions would capture, for example, op. 34c no. 16b. Op. 34c – 16b, Op. 10 and so on. The normalized expression is crucial as it allows multiple different ways of expression the opus numbers while providing a single and stable number to match with files or other databases.

Per-composer Catalog Numbers

Those are additional expressions that are keyed by composer. One of the additional capabilities are alternative numbers. Example, K. numbers for Mozart frequently contains two K. numbers (original catalog and then K6 number) separated by /. Also, CPE Bach has two catalogs Wq and H and both can map, with in this case, primary number H and alternate is Wq. Each composer can have a list of possible unique patterns to match various formats or usage,

Work Tagging

Before going any further, here is some information on how music files are tagged and where work identifier can apply and how some hierarchical structure can influence identification. The highest element is a “disk”. However, a disk can have multiple physical disks when part of a boxed set where all the disks have the same cover. If the boxed set is a box with separate CDs inside with different covers, then they would remain as individual disks. If the boxed set is a 4-CD boxset, then a virtual large disk would be created with track numbers remap linearly. Example, 4 CDs with each 4 tracks would have CD 2 renumbers 5-8, the third one 9-12 and so on.

Disks in tagging are NOT part of the IDv3 tags. In the regular world, “album” is used for that, but it is mostly meaningless in classical music and the work/movement additions were likely made by people who have no clue about classical music. Therefore, the second level uses “album” to separate works or collections of smaller pieces. So, disks are identified as a decoration on the “album.” The other important distinction between classical and popular music which drove the specs for tagging is interpretation. Large portion of a music collections has various interpretations. Example, Mozart’s 40th symphony could be interpreted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, James Levine, Herbert von Karajan or even have the same conductor having more than one recording in different time or with different orchestra. Or you could have a CD that was later on remastered in high resolution from the original master tapes. So, interprets are key in identifying albums.

Anatomy of an album name:

<composer>: <significant name> [variant] (<interpret>) <work decorations> {<resolution> <id>}A lot of that format comes from older devices with limited screen size, so the idea was to compact the information so that the most identifying factors are put as early as possible. Eventually, likely <composer> will be removed as it is redundant with the actual Composer field and less accurate.

Mozart: Symp. 40 (Harnoncourt) in g minor, K.550 {CD W-1450}

Mozart: Symp. 40 [arr. Chamber] (LSO Soloists) in g minor, K. 550 {SACD C-100}

Vivaldi: Conc. violin op. 8 - 1 (Dantone) in E major, RV265 “Spring” {HR E-222-S}| Mozart | Last name of composer. Not used by any automated portions of the system |

| Symp. 40 Conc. violin op. 8 – 1 | This is the significant name of the work. That is the portion that allows recognizing that it is the same work but either interpreted by different musicians or in different shapes or arrangements. Catalog numbers are frequently the identifying element or even the key. |

| [arr. chambre] | Square brackets provide a different angle to any work. Ex: [v. 1898] for a Brucker symphony, [v. piano] for a piano reduction of an orchestral work, [extract] informs that this is not the full work, but an extract… |

| Harnoncourt, LSO Soloists | The conductors interpreting the work. When working with chamber music or solo instruments, it is the players last name that will there, possibly more than one separated with /. |

| in g minor, K.550 in E major, RV 265 “Spring” | Additional information such as work nickname, key if it is not the significant identity, catalog number. In the case of the first concerto from The Four Seasons, the work is identified though both published opus number (and sub number) and also through it’s Vivaldi catalog number, in this case R. 265 once normalization map is applied. |

| {CD W-1450} {SACD C-100} {HR E-222-S} | This is where the “disk” appears. The first portion indicates the type. CD means 16 bit 44.1 khz recording that were most likely. MP3 means an MP3 origin. All others are implying high resolution. In that case, the disk id also provides information on the number of channels. C-100 implies a 5.0 or 5.1 multi channel recording. E-222-S implies stereo. You could also see something like B-260-Q that implies 4.0 recording. SACD means it is a physical SACD that is the origin of the files. HR means it is coming from online acquisition of high-resolution music. The letter in front does have additional info on the source and frequently historical. C-100 implies that SACD used to be the slot 100 on the 3rd 400 SACD jukebox used to play those disks. W just means that CD was downloaded from the internet and it was the 1450th one! |

Tracks, work structure and inferred works

Since the album already contains how to identify the work, most track names are just the movement like “I. Allegro”. Example of a 2-CD high resolution download (merged as one super CD):

| 1 | I. Adagio – Allegro | 10:42 | Mozart: Symp. 39 (Harnoncourt) in Eb major, K.543 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 2 | II. Andante con moto | 7:36 | Mozart: Symp. 39 (Harnoncourt) in Eb major, K.543 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 3 | III. Menuetto – Trio | 3:51 | Mozart: Symp. 39 (Harnoncourt) in Eb major, K.543 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 4 | IV. Allegro | 8:21 | Mozart: Symp. 39 (Harnoncourt) in Eb major, K.543 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 5 | I. Molto allegro | 7:27 | Mozart: Symp. 40 (Harnoncourt) in g minor, K.550 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 6 | II. Andante | 12:08 | Mozart: Symp. 40 (Harnoncourt) in g minor, K.550 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 7 | III. Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio | 4:19 | Mozart: Symp. 40 (Harnoncourt) in g minor, K.550 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 8 | IV. Finale. Allegro assai | 10:37 | Mozart: Symp. 40 (Harnoncourt) in g minor, K.550 {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 9 | I. Allegro vivace | 13:00 | Mozart: Symp. 41 (Harnoncourt) in C, K.551 “Jupiter” {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 10 | II. Andante cantabile | 9:30 | Mozart: Symp. 41 (Harnoncourt) in C, K.551 “Jupiter” {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 11 | III. Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio | 5:14 | Mozart: Symp. 41 (Harnoncourt) in C, K.551 “Jupiter” {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

| 12 | IV. Molto allegro | 11:39 | Mozart: Symp. 41 (Harnoncourt) in C, K.551 “Jupiter” {HR E-222-S} | Symphonies |

The above is the most typical case. Please note that the work identifiers (K. 543, K, 550, K. 551) can be induced from “album”.

Now, some larger work can be composed of many tiny works or you want to group smaller works into some “various piano pieces” or such. Example for two parts inventions:

| 1 | No. 1 In C, BWV 772 | 1:31 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 2 | No. 2 In C Minor, BWV 773 | 1:52 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 3 | No. 3 In D, BWV 774 | 1:22 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 4 | No. 4 In D Minor, BWV 775 | 0:58 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 5 | No. 5 In E Flat, BWV 776 | 1:39 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 6 | No. 6 In E, BWV 777 | 3:45 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 7 | No. 7 In E Minor, BWV 778 | 1:33 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 8 | No. 8 In F, BWV 779 | 0:58 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 9 | No. 9 In F Minor, BWV 780 | 1:43 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 10 | No. 10 In G, BWV 781 | 1:03 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 11 | No. 11 In G Minor, BWV 782 | 1:13 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 12 | No. 12 In A, BWV 783 | 1:45 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 13 | No. 13 In A Minor, BWV 784 | 1:12 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 14 | No. 14 In B Flat, BWV 785 | 1:36 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} | |

| 15 | No. 15 In B Minor, BWV 786 | 1:15 | Bach: Inventions of two parts (K. Gilbert) {CD W-258} |

In the case, although that Back works can be grouped as “two parts inventions” in all catalogs or databases, they are considered as 15 independent works numbered 772@786.

Now what if those little individual pieces are multitrack themselves. A frequent case. He’s how the “well-tempered harpsichord book 1”.

| 1 of 96 | [No 1 in C, BWV 846] I. Prelude | 2:00 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 2 of 96 | [No 1 in C, BWV 846] II. Fugue | 1:31 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 3 of 96 | [No 2 in c, BWV 847] I. Prelude | 1:26 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 4 of 96 | [No 2 in c, BWV 847] II. Fugue | 1:20 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 5 of 96 | [No 3 in C#, BWV 848] I. Prelude | 1:20 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 6 of 96 | [No 3 in C#, BWV 848] II. Fugue | 2:16 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 7 of 96 | [No 4 in c#, BWV 849] I. Prelude | 1:53 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

| 8 of 96 | [No 4 in c#, BWV 849] II. Fugue | 2:45 | Bach: Well-tempered I (Butt) {HR E-182-S} |

When track names are in the pattern of “[<inferred work>] <real track name>” the tracks under the name <inferred work> are considered part of an “inferred work”. In this example, there are four inferred works numbered BWV 846@849. In this case, catalog number would be determined from those inferred works.

A last, but not least pattern is when the enveloping number is the “album” (or in the inferred work), but the sub-number is in the track.

| 1 | #1 In C | 0:56 | Mozart: Five contradance, K.609 (Krysa) {CD BLI3K2-51} |

| 2 | #2 In E Flat | 0:47 | Mozart: Five contradance, K.609 (Krysa) {CD BLI3K2-51} |

| 3 | #3 In D | 1:09 | Mozart: Five contradance, K.609 (Krysa) {CD BLI3K2-51} |

| 4 | #4 In C | 2:51 | Mozart: Five contradance, K.609 (Krysa) {CD BLI3K2-51} |

| 5 | #5 In G | 1:20 | Mozart: Five contradance, K.609 (Krysa) {CD BLI3K2-51} |

In that case, the five tracks will have catalog numbers K. 609 – 1 though K. 609 – 5. # could be replaced by various “no.” “no” “No. “.

There are a few others way to influence work numbers that is using the “grouping” tag for a proprietary additional tagging.

[Opus=K. 609]

[Opus=K. 609#3]

[Partition=6b] (we will look at this later with scores and incipitsDisk Information

There are three key pieces of information that are tied to disks.

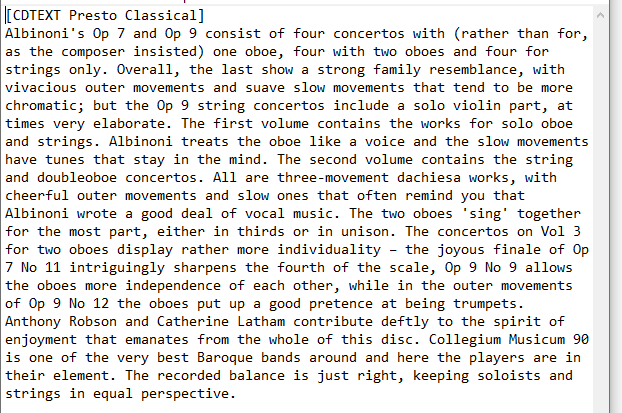

CD documentation

That can be coming from label sites that describes the cd itself or frequently contains some bio of the composers or the era in which the works were created. These information are tagged by source (booklet, critics or any other source) and language and it is available in more than one language. That information is extracted from specially formatted “lyrics” (we will have a closer look on those formatted lyrics in a special section later).

Booklets

The booklets that are tied with a CD are often available as PDF on the internet and usually supplied with any purchased CD downloads. For those that are not available as PDF, it is possible to scan all the pages and transform it using a special hidden software into a series of “pages” jpgs that need to be placed in a directory. Each PDF file or the directory of jpgs need to be named “<disk ID># Any description” in placed in the “Booklets” directory.

Ex: C-312# Bach, Cantates 91, 57, 151, 122 (Kuijken)

Ex: J-0367# Harvey, Piano Trio; Advaya; Dialogue and Song; Etc. (Fibonacci).pdf

Covers

For the covers, it is straightforward. File must be named <disk id>.jpg in the “Covers” directory.

Label

One of the possibly useful tagging for the future (if label catalogs become more easily accessible for further decoration) is to tie the disk with it’s source. This is done in the “sub tagging” field high jacking “grouping” tag. The label tag is essentially [Label=<label>:<catalog number>]. Example [Label=Erato:9029593044] points to the Bach’s complete keyboard work interpreted by Zuzana Ruzickova (20 CDs).

Recap

Recap for disk information. Coming from 3 different sources: CDTEXT references in formatted lyrics (typically on the first track of the disk), the “Booklets” and “Covers” directories using the “disk ID” as key.

People Information

Composers and interprets are attached to each track or work. To increase the quality of the interaction with the music applications, and to add a few more dimensions for browsing (ex: era, country), composers and interprets can be “decorated”.

Composers

Composers are attached to a “album” (work) in the “composer” tags. Although technically it is not enforced, having different “composers” for one work would give some weird results. Composers are always identified as <Last Name> (First Name) such as “Mozart (Wolfgang Amadeus)”.

The “Composers” directory contains three main sub-directories (there is a 4th one to be discussed later):

Bios

Each “documented” composer will have a single xml file providing the following information: Country, Era, Birth, Death and documents or source of documents like wiki page. There can be as many as needed, provided the pair “language / source” is unique.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?><composer Name="Myaskovsky (Nikolai)" Country="Russe" Era="Moderne" Birth="1881/04/20" Death="1950/08/08">

<bio language="en" source="wikipedia" page="/wiki/Nikolai_Myaskovsky" />

<bio language="fr" source="wikipedia" page="/wiki/Nikola%C3%AF_Miaskovski" />

</composer>On top of that document created by the Music Manager, additional decorations can be added by creating a sub-directory with the composer name and then various TXT files with the same source/language restrictions. English is the default language presumed.

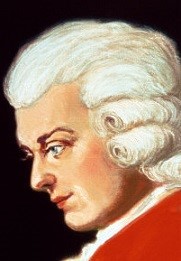

Images

As is probably obvious, you can add a <composer>.jpg or <composer>.png in the Images sub-directory so the client applications can automatically show the composer’s image on screen. It is also possible to add more than one pictures by adding “ – 1” “ – 2”… to the composer name.

TBD

This is simply a directory full of yet undocumented composers that are referenced in the library tags, but not yet “processed”.

Interprets

Interprets can have many roles… and literally play a role in an Opera. There are conductors, orchestras, soloists and singers. We have seen earlier that some interprets can be inferred from the album name and help differentiate interpretations of the same work. However, it is not enough. The “comments” field of the IDv3 tags is used to provide more information. Here are a few examples:

[TAGS]

Conductor=Krysa (Taras)

Orchestra=Slovak Sinfonietta[TAGS]

Conductor=Spanjaard (Ed)

Orchestra=European Sinfonietta

Soloist=Heyden (Francine van der) [soprano][TAGS]

Ensemble=Quartetto Italiano

Member=Borciani (Paolo) [violin]

Member=Pegreffi (Elisa) [violin]

Member=Farulli (Piero) [viola]

Member=Rossi (Franco) [cello][TAGS]

Conductor=Janowski (Marek)

Orchestra=Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin

Choir=Rundfunkchor Berlin

Soloist=Vogt (Klaus Florian) [ténor:Lohengrin]

Soloist=Dasch (Annette) [soprano:Elsa]

Soloist=Resmark (Susanne) [mezzo:Ortrud]

Soloist=Grochowski (Gerd) [baritone:Friedrich von Telramund]

Soloist=Bruck (Markus) [baritone:Der Heerrufer des Konigs]

Soloist=Groissbock (Gunther) [basse:Heinrich der Vogler]All those patterns influence the way the interprets are shown on the various client applications.

It is possible to change the interprets for each track to be very specific on who is involved with each track (example, characters and singers for a specific aria). But that is a bit messy. Instead, you can add an ID at the end of each soloist like for that last example:

[TAGS]

Conductor=Janowski (Marek)

Orchestra=Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin

Choir=Rundfunkchor Berlin {CH}

Soloist=Vogt (Klaus Florian) [ténor:Lohengrin] {T}

Soloist=Dasch (Annette) [soprano:Elsa] {S}

Soloist=Resmark (Susanne) [mezzo:Ortrud] {M}

Soloist=Grochowski (Gerd) [baritone:Friedrich von Telramund] {BT1}

Soloist=Bruck (Markus) [baritone:Der Heerrufer des Konigs] {BT2}

Soloist=Groissbock (Gunther) [basseHeinrich der Vogler] {B}For each track, you can specify, for example {S,BT1,CH} and the clients will know that conductor and orchestra never change throughout the performance, for the specified track the soprano playing the role of Elsa is on stage with Friedrich von Telramund and the choir is also used.

Bios and Images

The Interprets directory mirrors the same exact “Bios”, “Images” and “TBD” structure and ways of navigating as the Composers, which the potential exception that interprets also have a “instrument” associated with them.

Recap and small examples

Here are a few examples of what can be seen on screen. The first is a simple solo performer (Zuzana Ruziicka) interpreting Bach’s first French suite for harpsichord. The small “documents” icon will be discussed when tackling “work information”. (Note the 1720-22? Small text, we will learn more about those with “Catalogs.”

The second example shows Quartetto Italiano with “ensemble members” expanded (application can be told to only show the name and image of the group). Note: since porting to Xamarin, there is still much to do to improve display of the interprets, especially on the ease of reading the text when an image is overlapping.

Some more examples of different arrangements. Also note in this next one how movement numbered IIa, IIb, IIc… are displayed in a smarter way. And, that when there is no picture for an interpret (or a composer), the album art is used to represent them.

Work Information

Now that we have seen how the identity of works is determined, how information can be attached to disks and how we can use people decorations to improve how playlists are viewed, works and tracks themselves can have multiple sources of “decoration”.

- Scores & Incipits

- Notes

- Catalogs details

- Lyrics

Scores and Incipits

Since incipits are usually created from scores, we can describe them in the same section. But first, let us discussed scores. They all start from a PDF file. Some were processed to capture works and sequencing in a more precise manner as a series of bitmaps that could eventually also be decorated with repetitions and alternatives to make it easier to follow through a score as the music is playing. But right now it is mostly about curiosity than anything else.

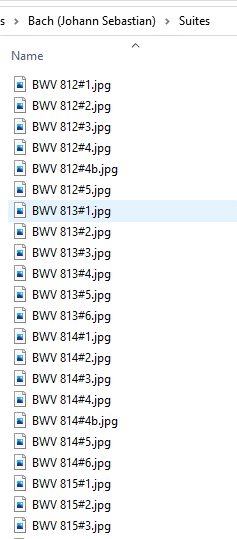

Identification and mapping

Scores are separated by composers. In the Scores directory, you can find one sub-directory which bares the name of a composer for each composer with a score. Within that directory, further classification is optional, but the naming of the files is critical. Every score (PDF file or directory of images for processed scores) starts with an opening square bracket and follows this format:

[<movement>.<sequence>] <significant work name> {<optional flags>}@<work identifier>

If <movement> is $, then the score is for the full work. <movement> can also be P<number> or A<number> for works that are divided into parts or acts (tagged using “inferred work” technique described earlier). Follows an example of Brucker’s 1st and 5th symphonies. PDF files always have a sequence number of $ as they are self-contained. Processed scores are using the sequence number as “page number”.

The first example is whole work, the second one only shows the 2nd movement.

[$.$] Symphony No.1 in C minor@WAB 101.pdf

[2.$] Symphony No.5 in B-flat major@WAB 105.pdfAnd here is a an actual manuscript as indicated by the {M}:

[2.$] Symphony in F minor{M}@WAB 99.pdfThe following is a piano reduction of the 6th symphony as indicated by {A} (arrangement) and the [piano] supplemental information.

[$.$] Symphony No.6 in A major [piano]{A}@WAB 106.pdfAs can easily be surmised, works by Bruckner are identified by the WAB catalog number. Albums tagging for his works usually contain a WAB reference, normalized by the “Maps” discussed earlier. This is the key piece of information to tie it all together.

- Based on album, check for an opus number. If there is one, try to match with a score

- If no match, then try the above but with composer-specific catalog id

- If no match, then try the ‘significant work name’ and see if it matches the significant name of file

There are other attempts being made that combines work sub numbers and sometimes also movement numbers, especially if those were determined with a “No. X” track name.

Processed Scores

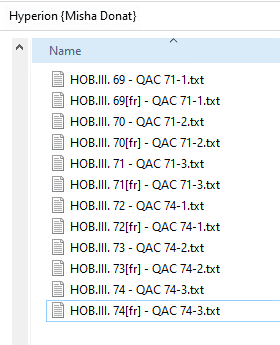

Processed scores are slightly different but have a lot in common. For example, here is the directory containing the processed score of the first keyboard sonata from Domenico Scarlatti:

S. clavecin K001@K. 1 [L]Note the [L]. This indicates if the resulting images are more landscape or portrait [P]. And here is the content of the directory

Here is the “original” PDF, fully flagged like all the other PDF scores. This is crucial because it is the file that will be “found” by the server and then, because of the [L] or [P] ending of the parent directory infer it is processed and then gather the images.

Sequence 1

Sequence 2

Until the last one

One of the great advantages is for partition that contains multiple pieces and where the separation between the works happens often in mid-page to save on paper. It makes the PDF hard to map with the specific work in the current playlist.

The [X] factor

One final case. When a score directory ends in [X], it means that it is a work grouping individually numbered work (like we saw with the two-parts inventions earlier). So an [X] directory means that not only the works have been processed, but that their “identifiers” are attached to the individual images as you can see here for the mentioned two parts inventions.

Incipits

Incipits have some similarities to scores, but are more specific and with a wider scope. An incipit is essentially the first set of staves that open a work, a movement or a sub-divided portion of a work. The first sequence of Scarlatti’s K. 1 as shown earlier is an incipit. In this case, it is an automatic one as it was already processed completely.

Like scores, the Incipits directory is sub-divided by composers. Within the composer directory, there is no imposed order except that large composers like Bach, Beethoven and Mozart do benefit from grouping. Incipits are jpg files that are following this pattern:

<identifier>#<movement>.jpg

If the work is in a single movement, then only <identifier> will be used. The identifier is almost always an opus number or a composer-specific catalog number. Movements can have separator like Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb like for Saint-Saens 3rd symphony with organ. In this case, the movement numbers would be 1, 1b, 2, 2b. The reason to omit the a for 1&2 is in case you have a recording only showing I and II with no track separation. This is very common and there is a large complexity from works not being numbered the same way. Example, some recording of l’Estro Harmonico show I, II, III while some others will show 1@5 with semi-divided movements are explicit tracks. It is important to review those works and likely re-tag all the files with I, II, III and likely Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, III and have the incipits properly marked.

Example, the first French suites with incipit for each movement:

Incipit BWV 553.jpg

Work descriptions, notes and lyrics

The main source of work descriptions comes from codified “lyrics” tag. You can pile several sections in the lyrics, each one that can have a source and a language, which default to “booklet” for source and “EN” for English for language.

The possible tags:

Lyrics

Usually at the top of the field, when there are lyrics, they can be very simple. Here is a typical Sanctus in three languages:

[LYRICS:LT]

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi,

miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi,

dona nobis pacem.[LYRICS:FR]

Agneau de Dieu qui portes les péchés du monde,

aie pitié de nous.

Agneau de Dieu qui portes les péchés du monde,

donne-nous la paix.[LYRICS:EN]

Agneau de Dieu qui portes les péchés du monde,

aie pitié de nous.

Agneau de Dieu qui portes les péchés du monde,

donne-nous la paix.When loading albums and tracks for the media server, client applications can supply a list of preferred languages. The first entry in the tags is considered the “original” (latin in this case).

Album, disk and tracks

Although there is no specific enforced orders, the next three tags are usually present in the first track of their grouping. For example, disk documentation will usually be in the first track for the disk, the album documentation in the first track of the work and the track documentation, well, in the track itself.

Example of the first track of Alessandro Scarlatti’s cantata “Euridice dall’Inferno” recording by Ars Lyrica Houston.

[LYRICS:IT]

Del lagrimoso lido su l’infocate arene, Orfeo, caro consorte, mi lasci, e m’abbandoni, preda d’eterno duolo e non di morte. Qui, dove inalza il trono il foco eterno possono gl’occhi tuoi sgombrar l’orrore e le fiamme d’Inferno: non devi paventar, s’ardi d’Amore.[LYRICS:EN]

On the burning sands of the mournful shore, Orfeo, dear consort, you leave and abandon me, prey to eternal grief – not death. Here where eternal fire raises the throne, your eyes can dispel the horror and the flames of hell: you need have no fear if you burn with love.[CDTEXT]

Alessandro Scarlatti, the great master of Baroque opera seria, was even more highly regarded by his aristocratic patrons for his exquisitely crafted chamber cantatas. Over the course of an exceptionally long and productive career, he wrote more than six hundred such works for performances at the homes of wealthy Roman patrons, including the exiled Queen Christina of Sweden, Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli, and cardinals Benedetto Pamphili and Pietro Ottoboni, whose insatiable appetite for cantatas brought the genre to its apex. Virtually all these cantatas are about love, its joys, perils, risks, and rewards, and in their librettos one finds familiar figures from history, myth, and the pastoral world of nymphs and shepherds.[ALBUM]

Both sources of Euridice dall’Inferno carry the date 17th June 1699, situating it in the middle of Scarlatti’s output, just after his decisive turn toward da capo procedure in aria design. (The tripartite da capo form, which includes a return to the first section of music and text, gives the singer an opportunity to embellish freely the melodic line while reinforcing the aria’s fundamental Affekt.) One of Scarlatti’s finest cantatas, Euridice consists of three beautifully calibrated recitative-aria pairs which explore the eponymous nymph’s uncertain fate in the underworld. Scored simply, for soprano and continuo (melody instruments are the exception in this repertoire), the work nevertheless conveys a wide range of emotion, from despair to hopefulness. In contrast to better-known operatic treatments of this tale, Scarlatti’s heroine is no blushing bride. Though still vulnerable and dependent on Orpheus’ musical powers to win her release, this Euridice projects courage, steadfastness, even fearlessness as she awaits her lover’s rescue.In that example, there is no specific documentation of each movement. Just the lyrics for each subsequent tracks. Here we see track 2 of a disk of piano concertos by Shostakovitch which is the first movement of the second concerto. So no, CDTEXT (it is in the first track), but but both work and movement documentation.

[ALBUM]

The Piano Concerto No.2 in F major, was written in 1957 for Shostakovich's son Maxim, who gave the first performance of the work on his nineteenth birthday. The work has about it a youthful appeal for performers and audience alike.[TRACK]

The lively first movement opens with a brisk march, leading to a gentler second theme. The material is developed in the central section, and a cadenza ushers in again the principal theme to bring the movement to an end.File-based work descriptions

In addition to work descriptions that are more booklet-based (and there sometimes not apply to other interpretation of the same work), there is a directory structure to supply that information.

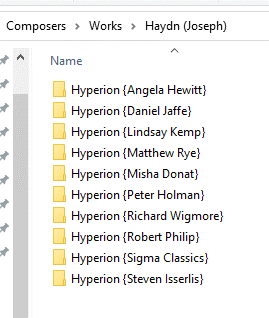

It is the “fourth” sub-directories under “Composers”. That sub-directory (called “Works”) is further divided by, once again, composers!

Under a composer, work is first organized by the source of the documentation (copyright!!) in the following format <origin> {<writer>}. For example, under Joseph Haydn, you will find:

Under each of those “source” directories, the works are organized as one wishes, but the actual final documents must follow this naming convention: <work identifier>[<language>] – <unused description>.txt.

Example:

Inside those files, documentation follows a simple pattern. Free text until the first paragraph starting with [<movement>]. The first part is considered the “work part” (equivalent to the [ALBUM] section of the codified lyrics). Then those text are matched with the movement numbers from the tagging and used as “TRACKS” description. If no match is found the text is added to the album. Here’s an example from Debussy’s Estampes:

Estampes (Engravings) is the title of the triptych of three pieces which Debussy put together in 1903. The first complete performance was given on 9 January 1904 in the Salle Erard, Paris, by the young Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, who was already emerging as the prime interpreter of the new French music of Debussy and Ravel. The first two pieces were completed in 1903, but the third derives from an earlier group of pieces from 1894, collectively titled Images, which remained unpublished until 60 years after Debussy’s death, when they were printed as Images (oubliées). Estampes marks an expansion of Debussy’s keyboard style: he was apparently spurred to fuse neo-Lisztian technique with a sensitive, impressionistic pictorial impulse under the impact of discovering Ravel’s Jeux d’eau, published in 1902.

[1]

The opening movement, ‘Pagodes’, is Debussy’s first pianistic evocation of the Orient and is essentially a fixed contemplation of its object, as in a Chinese print. This static impression is partly caused by Debussy’s use of long pedal-points, partly by his almost constant preoccupation with pentatonic melodies which subvert the sense of harmonic movement. He uses such pentatonic fragments in many different ways: in delicate arabesques, in two-part counterpoint, in canon, harmonized in fourths and fifths and as an underpinning for pattering, gamelan-like ostinato writing. Altogether the piece reflects the decisive impression made on him by hearing Javanese and Cambodian musicians at the 1889 Paris Exposition, which he had striven for years to incorporate effectively in music. In its final bars the music begins to dissolve into elaborate filigree.

[2]

Just as ‘Pagodes’ was his first Oriental piece, so ‘La soirée dans Grenade’ was the first of Debussy’s evocations of Spain—that preternatural embodiment of an ‘imaginary Andalusia’ which would inspire Manuel de Falla, the native Spaniard, to go back to his country and create a true modern Spanish music based on Debussyan principles. Debussy’s personal acquaintance with Spain was virtually non-existent (he had spent a day just over the border at San Sebastian) and it is possible that one model for the piece was Ravel’s Habanera. Yet he wrote of this piece (to his friend Pierre Louÿs, to whom it was dedicated), ‘if this isn’t the music they play in Granada, so much the worse for Granada!’—and there is no debate about the absolute authenticity of Debussy’s use of Spanish idioms here. Falla himself pronounced it ‘characteristically Spanish in every detail’. ‘La soirée dans Grenade’ is founded on an ostinato that echoes the rhythm of the habanera and is present almost throughout. Beginning and ending in almost complete silence, this dark nocturne of warm summer nights builds powerfully to its climaxes. The melodic material ranges from a doleful Moorish chant with a distinctly oriental character to a stamping, vivacious dance-measure, taking in brief suggestions of guitar strumming and perfumed Impressionist haze. There is even a hint of castanets near the end. The piece fades out in a coda that seems to distil all the melancholy of the Moorish theme and a last few distant chords of the guitar.

[3]

‘Jardins sous la pluie’ is based on the children’s song ‘Nous n’rons plus au bois’ (We shan’t go to the woods): its original 1894 form was in fact entitled Quelques aspects de ‘Nous n’rons plus au bois’. The two versions are really two distinct treatments of the same set of ideas, but in ‘Jardins sous la pluie’ Estampes the earlier piece has been entirely rethought. The whole conception is more impressionistic, and subtilized. The teeming semiquaver motion is more all-pervasive, the tunes (for Debussy has added a second children’s song for treatment, ‘Do, do, l’enfant do’) more elusive and tinged sometimes with melancholy or nostalgia. The ending of the piece is entirely new. What it loses, perhaps, in child-like brashness the music gains in poetry and technical focus.Catalogs

This feature is about the actual catalogs of works for the composers for whom it is available. So it is about additional decorations (ex: date and location of composition) and about having access to information on music not yet in the library and seeing what is missing. Each composer catalog is held in an xml file baring the composer’s name in the “Catalogs” directory, for example: Mozart (Wolfgang Amadeus).xml. Catalogs can be coming from multiple sources and aggregated by the Music Manager.

Here’s an example of an entry:

<work primary="K. 5" secondary="K. 5" musickey="F major" location="Salzburg" genre="Keyboard" date="5 July 1762" distribution="pf">

<title>Minuet in F for Piano</title>

<note source="IMSLP">No.10 in Nannerl's Music Book</note>

<link source="IMSLP">/wiki/Minuet_in_F_major,_K.5_(Mozart,_Wolfgang_Amadeus)</link>

<link source="Wikipedia">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nannerl_Notenbuch#Minuet_in_F.2C_K._5</link>

</work>First, addressability. For Mozart, the primary key is the original Kochel number while the secondary is the new K6 number from the 6th revision of the catalog. This does mean for work discovered after the first catalog that an entry could have a secondary key and no primary key. No worries, the music server can deal with it! Mozart wrote this piece in F major and, apparently on July 5th, 1762 in Salzburg. This was written for pf (piano forte) and its title is “Minuet in F for Piano”.

Those work descriptions can have multiple notes and links. As can be inferred, the catalog was essentially built on the catalog in IMSLP (where are the scores come from!). It was then merged with the catalog found in Wikipedia which mostly added a URL to the page in Wikipedia pertaining to the work.

Now, based on the key “K. 5” we find the following score:

And the following incipit (taken from a different, more breezy score):

Now a quick example on what it looks like (rough UI) in a Xamarin-based client application. As you can see in the next screen shot, we easily find K. 5 (sorted by catalog number). You can see in the left that there is a least one CD in the music library.

Now selecting our minuet, we now see that there are two interpretations available. (At some point, more info needs to be added to those interpretations such as… the interpret!). In both cases, those were tracks in a grouping album “Various piano” in one case and “Youth piano pieces.” So it is the track-level “catalog number” mapping that found these tracks. Also, one is using KV 5 and the other K.5. Both are internally set to K. 5.